When a natural or man-made disaster strikes it can have an adverse effect on people’s well-being, property and the environment. Hazardous incidents can include events such as wildfires, floods, earthquakes, chemical spills. When people’s well-being is at imminent risk it is common practice to attempt the evacuation of the affected area and move those that are, or may be, affected to safety. The extent to which an area needs to be evacuated depends directly on the type of event, the severity of the incident, the spread of the hazard.

The complexity of the evacuation process

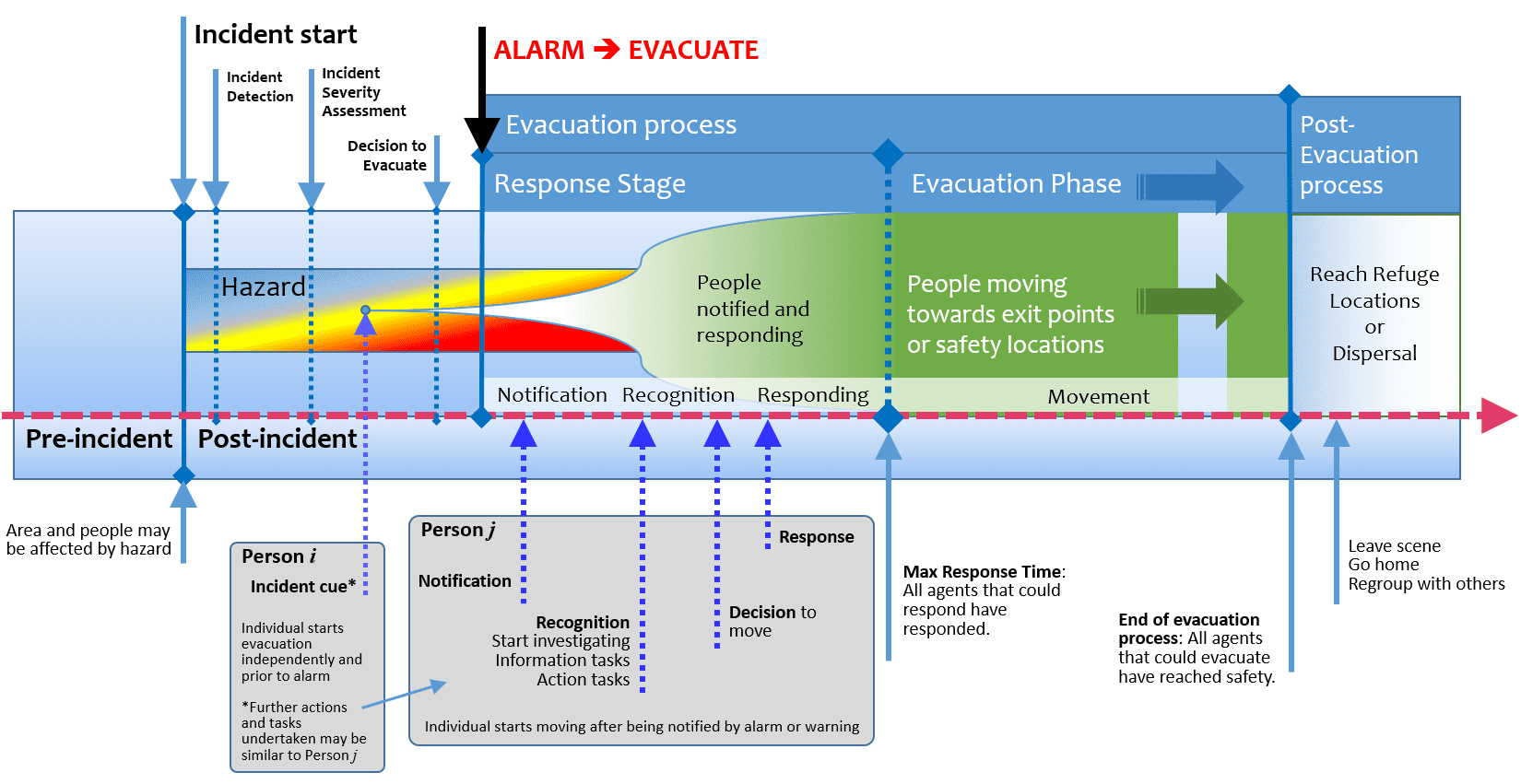

The evacuation process is typically complex and involves a number of agencies, several stages and a combination of factors which can influence its efficiency and the evacuees’ safety. This complexity is evident across multiple scales, from incidents involving a single building to a full scale city or area. Some phases or stages are distinct and sequential while others may overlap. These will be examined in turn. The figure below is an attempt to capture the main elements of the evacuation process from the time that an incident starts up to the end of the evacuation and the post-evacuation process. The diagram depicts the process of a large scale evacuation from the evacuees’ perspective. The events and stages described can be represented in the state-of-the-art EXODUS evacuation model. EXODUS is an Agent Based Model (ABM) that attempts to simulate the evacuation process from a closed structure or a large open area taking into account individual’s characteristics, the layout of the evacuation area and the environmental conditions that may affect the population.

Non- modifiable and modifiable event specific factors

For any evacuation there are several non-modifiable and modifiable event specific factors directly related to the incident, the reaction of the population and the performance of that population, that determine the eventual evacuation performance and efficiency.

Non-modifiable factors may include the time of the incident, the type of incident, the severity of the incident. There is little that can be done to control or modify any of these factors. Possible exceptions however could be for specific events where preventative measures have been employed, before an incident takes place that may mitigate the effects of a developing hazard (e.g. wildfire suppression attempts).

Modifiable factors include incident detection time, training and preparedness level of authorities and first responders, alarm and warning type, notification time, people’s response time, evacuation procedures and people’s familiarity with those. All these factors can have a significant impact on the evacuation process but may be improved or optimised increasing the evacuation efficiency. This can be achieved by assessing their impact and duration through the EXODUS evacuation model. This information can then help crisis managers in optimising evacuation procedures and to quicken or minimise the duration of the modifiable factors improving in turn the evacuation efficiency.

Stages of the evacuation process

The decision to evacuate needs to consider the risks from the hazard, the availability of resources to manage the evacuation, the means of communicating the need to evacuate, the population demographics, familiarity of the population in question with the area, the terrain and the evacuation procedures.

In order to better understand the evacuation process, it is worth splitting it into stages and examine briefly each one in turn. For any incident there are two main stages, namely the events that led up to the incident and events that take place after the incident. These two stages are broadly defined as pre-incident and post-incident stages.

While pre-incident events may, and most often do, influence post-incident outcomes, for example, via appropriately employed preventative measures, the main interest is on post-incident events and how appropriate mitigation measures may improve the evacuation efficiency.

Post incident stage

The post-incident stage includes several events of interest including: incident detection (if applicable), incident severity assessment, decision to call for evacuation and alarm or command to evacuate. It also includes the deployment of the emergency services and first responders required in the disaster area, such as firefighters, police and ambulance crew. Once the alarm is given the evacuation process is considered to have started. Note this is a process that encompasses a series of events and stages that the evacuees are affected by or engage in. It is also worth noting that while the majority of the population may start their evacuation activities after the alarm or verbal warning is issued, a proportion of the population may respond independently by observing incident cues, notify others and start the evacuation prior to the raising of the alarm.

The evacuation process is, in turn, split in two main parts, the response stage, also known as the pre-movement phase, and the evacuation phase, also known as the movement phase.

Response stage

The response stage includes notification, recognition, and decision phases and ends when the evacuees respond and purposefully start moving towards a location of safety. During the notification phase the individuals are notified of the incident by hearing the alarm, observing other incident related cues (e.g. fire, smoke), or get notified for the need to evacuate by the authorities or various communication channels (e.g. mass media, mobile phone services). Once a person is notified it is assumed that they will enter a recognition phase. Here the individual will start investigating, will attempt to seek information and will start the evacuation response. The person will thus engage in information (e.g. what is the incident related to) and action tasks (e.g. seek for, and group with, family members, collect belongings), may decide which evacuation route to follow and which exit point to use. Finally, at some point the person will decide to start evacuating. A person’s response phase ends when that person has started purposeful movement towards an exit location or place of safety. This is when that person’s evacuation phase starts. The overall response stage ends when all the people that could have responded to the call for evacuation have responded, i.e. have started purposeful movement towards a location of safety. This point in time denotes the maximum response time. Overall, the evacuation phase starts when the first person responds to the evacuation call.

While each person has their own response agenda and evacuation phase, it is worth noting that people generally do not all respond at the same time so people’s participation in a specific phase can overlap with a different phase that other people are currently engaged in. For example, while someone is in their recognition phase they may warn others causing them to start their notification phase.

During the evacuation phase the individual attempts to reach safety while interacting at the same time with those around him, the evacuation area and the environmental conditions. During this phase the individual may engage in a variety of tasks including, threat avoidance, congestion avoidance, route selection, group formation, interaction with authorities and information providing sources (e.g. signs and mass media and mobile phone notifications). The end of the evacuation stage is reached when all those that could have evacuated have reached a location of safety. This also defines the evacuation time. Once the evacuation phase is deemed to be complete, post-evacuation activities and processes take place. These may include, depending on the situation, dispersing in the surrounding area, moving to a refuge location or regrouping with family members or friends, etc.

The evacuation process is thus heavily influenced by human behaviour, the training received by crisis managers, the ability of officers located in the field to follow the approved evacuation procedures, the notification methods, the public’s knowledge of the area and evacuation procedures, the perceived severity of the hazard products, the perceived seriousness of the event, the public’s perceived authority of the officers etc.

When analysing an evacuation process, it is important to examine the modifiable factors mentioned earlier as these can, in many cases, be improved upon.

- Type of alarm – The type of alarm and verbal warning used can have a significant effect in urging people to start the evacuation. The perceived severity of the event can be reinforced by those factors resulting in a faster response and start of evacuation.

- Appropriate and concise information – Providing appropriate information in a concise, authoritative and assertive manner can also hasten the response time of those warned. In terms of the events and procedures that follow, the alarm and warnings can have a positive impact by reducing ambiguity and confusion, and by promoting the available options that the people should take during the evacuation.

- Fire products, signs and mobile phones – In certain circumstances a similar effect, of hastening the response, can be achieved by people experiencing the incident’s cues first hand, for example, by observing fire products. Furthermore, the information relayed to the evacuation population through signs, mobile phones or mass media can also have a positive impact if the information quality follows similar procedures as with the alarm and verbal warnings and is not contradictory with information received by other means.

- Familiarity with warning systems – Conducting alarm sounding and warning tests increase the public’s familiarity with these systems. An increased familiarity may have a positive impact on the public’s response to the evacuation call. Conducting drills with first responders and crisis managers for training purposes improves their preparedness and ability to respond to a crisis, increasing the evacuation efficiency if and when it needs to take place.

Identifying the evacuation process through what-if scenarios

The EXODUS evacuation model allows crisis managers to simulate and examine various what-if evacuation scenarios. Its use can help identify the duration of the entire evacuation process (i.e. duration of response stage plus evacuation phase) mentioned above and thus help determine where improvements can be made by employing and testing in a simulation environment appropriate methods and procedures to minimise the modifiable stages of the evacuation process.

Mr Lazaros Filippidis is a senior research fellow with the Fire Safety Engineering Group (FSEG) of the Faculty of Architecture, Computing and Humanities of the University of Greenwich https://fseg.gre.ac.uk/. Within the IN-PREP project, FSEG manages the enhancement and adaptation of webEXODUS and urbanEXODUS to better and more accurately describe physical environments, people’s movement and behaviours and communicate with C2 environments. These elements are essential for evacuation simulation in planning, training and real time support and shall be integrated into the Mixed Reality Preparedness Platform.