IN-PREP HANDBOOK

Representative of a responder organisation

You are a respresentative of a first responder organisation and want to enhance the collaboration with other organisations?

You might be interested in one of following topics:

General Suggestions

Initial suggestions based on lessons learned in TTXs, FSXs,

IN-PREP workshops and end-user interviews:

“Interoperability is not about relinquishing power but enhancing cooperation.”

Overall, a step-wise approach should be taken to enhance collaboration:

- Assessing the Status Quo

- Develop a legal basis/ a governance framework

- Specify collaboration:

- Information sharing and related baseline procedures are essential

- Then joint planning needs to take place.

- Finally, training and exercise on the developed plans are needed. Ideally, joint training programmes are developed (which may also create cross-organisational efficiency gains).

Assessment/ Evaluation and feedback mechanisms should be established with a “Plan-Do-Check-Act” cycle in which the evaluation results are addressed.

Ideally, central funding should be made available

Lessons learnt about collaboration should be centrally collected and also shared with others (e.g. at EU level)

“Build the actions on evidence”

To enhance the Status Quo, several interview partners suggested starting with an assessment of the Status Quo. These assessments can come in different forms:

- A map specifying the range of bilateral agreements that may exist at the regional and local level

- A review of past events to analyse the strengths and weaknesses in inter-organisational collaboration

- A self-assessment based on the Interoperability Continuum to specify areas for future action.

The IN-PREP Interoperability Questionnaire can be found HERE

“A governance framework ensures that collaboration does not only depend on personal relationships.”

Develop a legal basis

As a next step, framework conditions for collaboration have to be set. In many cases, a legal basis has been created to facilitate collaboration. For example, the Netherlands have started the creation of their Safety Regions after the fireworks disaster in Enschede in May 2000 and the New Year’s fire in the ‘De Hemel’ bar in Volendam in 2001. These Safety Regions function as collaborative entities between several civil protection actors such as fire services, medical assistance and crisis management under one regional management board. The development of the Safety Regions furthermore acknowledged the increasing complexity of society together with emerging “forms of threats [including terrorism which] require a different type of approach, different partners and a different strategy.”[1] Similarly, in the UK, the Civil Contingencies Act 2004[2] provides a single framework for civil protection and seeks to reinforce partnership working at all levels.

Co-design Emergency Plans and (Standard) Operating Procedures

In a second step, plans and operating procedures can be created jointly by the relevant organisations. Several examples as to how this has been approached by certain sectors or countries but also on a multi-national basis are sketched in this handbook. Particularly for sectoral collaboration, it can save a lot of time and effort to build on existing SOPs. Capacities and functionalities could be described at a more abstract level in plain language to be understandable by all organisations. If needed, these can be specified by the individual organisations into their terminology.

It is important that a shared goal is to develop although institutional agendas may vary. The protection of lives should be the guiding principle in multi-agency settings.

The developed plans and SOPs should be linked with (national) risk assessments.

Training and exercising (joint) procedures are obviously an essential part of enhancing collaboration. To ensure that training and exercises are implemented regularly, a respective legal basis and related funding would be beneficial. Overall, “hard” and “soft” issues (technical/human) aspects have to be addressed.

The development of joint training courses helps to integrate collaboration deeply. In addition, it may help to save resources. Respective training may even be mandatory when wanting to move to the next career step.

Due to a frequent turnover in staff, training and exercises have to be implemented on a very regular basis, ideally every 9-18 months.

Involvement of actors:

- Ensure that all actors relevant for the scenario under consideration are involved in the exercise and particularly also its preparation. This holds also true for private actors such as (critical) infrastructure operators, the military etc.

- Early on, share your yearly exercise planning with partner organizations / private actors and give them the option to join in on certain exercises. This improves the possibility that they are able to get involved early in the exercise planning process.

In terms of individuals, ideally, they meet physically and get to know each other at the forefront to establish trust

Defining (joint) exercise goal and sub-goals:

Training goals need to be clearly defined. For example, the focus may be on the execution of whole plans or SOPs or the phase between the event and the creation of command lines, i.e. about the first 30 minutes of an event only. The latter obviously allows for more repetitions and scenario variations. The general approach then allows the identification of actors and scenarios etc.

Language:

- Identify a language that is shared by all participants; in the mid-term, respective language courses may have to be made mandatory for key actors

- Try to define a shared terminology.

- Partners should avoid using technical jargon and abbreviations. Wording for capacities / functionalities should relate on a more abstract level to what is needed and the respective liaison officers should translate into their internal wording.

- Build on established glossaries and initiatives to standardise communication.

Use of data:

Which data should be included in the exercise and can be shared with others? Also, invest in the trustworthiness of the data, and define clearly who is the owner/provider of the data to improve trustworthiness from the other involved actors.

The digital sharing of plans allows for a comparison of plans between organisations and even across local geographic boundaries. Ideally, reporting structures are similar to allow for better comparison. This again could be requested by respective legal requirements. Also, the sharing of lessons learned via a portal may be useful to keep track of learnings and re-integrate them into the governance framework and plans.

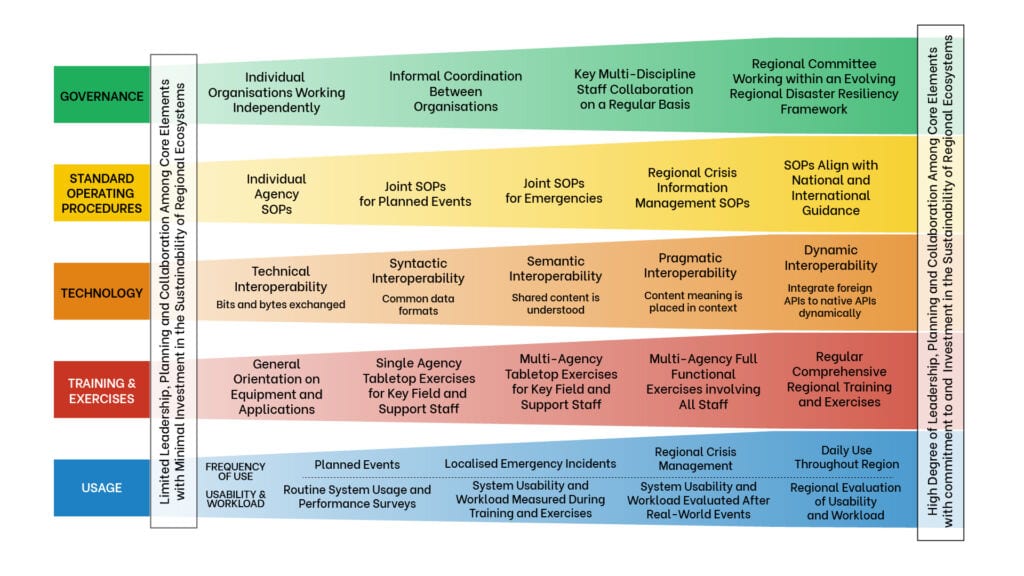

This section differentiates two different dimensions of cross-organisational incident response: national collaboration and international collaboration. Different dimensions of interoperability may be assessed making use of an interoperability matrix (continuum).

Cross-organisational collaboration at the national and international level

Cross-organisational collaboration or aspects of interoperability can be assessed and enhanced among several core domains. In the civil protection context, first steps have been made in the United States by developing an Interoperability Continuum. It was a result of the 9/11 attacks (Source HERE , p. 44, accessed 04.05.2020)

Thomas, J. & A. Squirini (n.a.): Measuring Systems Interoperability: A Focal Point for Standardized Assessment of Regional Disaster Resilience, p. 3, available (9.11.2020).

Multiple European states have adapted this approach of differentiating dimensions of interoperability such as Governance, Standard Operating Procedures, Technology, Training and Exercises and Usage. For example, the UK in 2009 (Source pdf), Belgium (Testelmans 2017), and France (Mannaioni et al. 2020) built on this approach.

Interoperability Questionnaire

*Please note that while this works in the Chrome browser, other browsers can have issues displaying interactive PDFs correctly. If you run into any issues, please download and complete it using Adobe Reader.

The Interoperability Matrix has been adapted into an interactive questionnaire so that users can gain a better understanding of how they are currently faring from an interoperability perspective and where they can use the Handbook to improve.

TransCrisis Survey

The TransCrisis survey helps to analyse whether, and to which extent, a particular organisation or policy sector is ready to face a transboundary crisis. It should be noted that this is not an IN-PREP product but an external link to a tool created by a partner project.

Governance

Governance Examples – National Examples For Legal And Organisational Bases In Cross-Organisational Collaboration

Ireland:

M.E.M. – Framework for Major Emergency Management (2006)

The Framework for Major Emergency Management was developed in 2005 and was adopted by Government decision in 2006. Its purpose is to set out common arrangements and structures for front line public sector emergency management in Ireland.

The document replaces the Framework for Co-ordinated Response to Major Emergency, which has underpinned major emergency preparedness and response capability since 1984. The new Framework was prepared under the aegis of the Inter-Departmental Committee on Major Emergencies, and has been approved by Government decision. The National Steering Group for the implementation of the Framework was established by Government Decision and replaces the Inter-Departmental Committee on Major Emergencies.

One of the key objectives of the Framework is to set out the arrangements and facilities for effective co-ordination

of the individual response efforts of the Principal Response Agencies to major emergencies so that the combined result is greater than the sum of the individual efforts. The Framework assigns responsibility for undertaking the coordination function clearly and unambiguously and requires it to be supported, so that it happens and is effective.

More Info:

UK:

Civil Contingencies Act (2004)

The Civil Contingencies Act 2004 provides a single framework for civil protection and seeks to reinforce partnership working at all levels.

It recognises that interrelated systems provide essential services in the UK and as networks have become more complex the range of challenges in maintaining resilience has broadened. Such complexity requires collaborative partnerships working towards common outcomes. Thus the expectation of the Act is that local authorities, the emergency services and the health sector, along with other key service providers, will collaborate and be able to provide normal services in crises, so far as is reasonably practicable.

In the UK, jont doctrine (JESIP) was developed following the Civil Contingencies Act and the Pollock Report.

Based on the Civil Contingencies Act as well as the associated Contingency Planning Regulations 2005 and guidance; the National Resilience Capabilities Programme (NRCP); and Emergency Response and Recovery ; the UK: Local resilience forums were developed.

There is more information for local resilience forums, including on self-assessment, peer review and improvement, in The role of Local Resilience Forums: a reference document.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=1&v=KQksEyGDRQg&feature=emb_logo

The key components of the Joint Doctrine are:

Principles for Joint Working – the principles we expect commanders to follow when planning a joint incident response

M/ETHANE – a common method for passing incident information between services and their control rooms Joint Decision Model (JDM) – A common model used nationally to enable commanders to make effective decisions together.

Local resilience forums (LRFs) are multi-agency partnerships made up of representatives from local public services, including the emergency services, local authorities, the NHS, the Environment Agency and others. These agencies are known as Category 1 Responders, as defined by the Civil Contingencies Act.

Netherlands:

Safety Regions Act (2010)

The Dutch Safety Regions Act has a long history that includes some very tangible events that have led to its adoption, such as the fireworks disaster in Enschede in May 2000

and the New Year’s fire in the ‘De Hemel’ bar in Volendam in 2001. The need for multidisciplinary cooperation involving both the traditional security partners and new partners grew, as citizens are entitled to expect that the public authorities will be able to work together in the event of disasters and crises.

In short, the effectiveness and professionalism of the emergency services in the Netherlands had to be increased. In order to bring this about, uniform service levels had to be established within cooperation areas (security regions) to facilitate mutual assistance and escalation.

The Safety Regions Act seeks to achieve an efficient and high-quality organisation of the fire services,

medical assistance and crisis management under one regional management board. The Act stipulates that as a common rule, safety regions must be structured on the same scale as the police regions. The Safety Regions Act lays the foundations for organising disaster and crisis management with the aim of better protecting citizens against risks.

More Info:

Sweden:

Stockholm Resilience Region

In the initiative the players will develop the ability to collaborate and cooperate through coordinated planning and decisions.

The players involved are the municipalities in Stockholm County (26), County Administration Board of Stockholm, Swedish Armed Forces, Swedish Coastguard, Police Authority in Stockholm Region, SOS Alarm, Ports of Stockholm, Stockholm County Council, Public Transport, Greater Stockholm Fire Brigade, Södertörn Fire and Rescue Services, Attunda Fire Services, and Swedish Transport Administration. The Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency, MSB, contributes national support and quality assurance of methods and technology from a holistic perspective.

More Info:

Governance Examples – Multi-National Examples For Legal And Organisational Bases In Cross-Organisational Collaboration

Council of the Baltic Sea States (CBSS)

Civil Protection Network (CPN)

CPN convenes annually at the level of Directors-General. The network’s chairmanship follows the CBSS Presidency rotation.

Purpose: Exchange views on ongoing activities and to coordinate joint measures in the field of civil protection, critical infrastructure protection and other emergency preparedness issues in the Baltic Sea Region. Additionally, the network meets annually at senior expert level and on ad hoc basis in different constellations in order to discuss particular issues or prepare joint projects.

Based on an extensive expert analysis of the situation in the region and consultations among all member states,

the Directors General for Civil Protection in the Baltic Sea Region adopted the Joint Position on Enhancing Cooperation in the Civil Protection Area at their 15th meeting in Iceland on 11 May 2017. It outlines prioritised areas in need of increased cooperation in the Baltic Sea Region to strengthen resilience and preparedness for various types of risks and threats. The positioning also encompasses the development of demand-driven and well-tailored training and education: The Baltic Leadership Programme of 2013-17 should be continued and developed amongst the lines as decided during 14th Meeting of Directors General for the Civil Protection in the Baltic Sea Region in Gdańsk on 8-9 June 2016. Additional training programmes may be developed for specific needs. The Baltic Leadership Programme seeks to create a network of key civil protection actors in the Baltic Sea region and equip them with the tools and information needed to manage cross-border collaboration and projects between diverse organisations in an intercultural context.

Euregion Meuse-Rhine Incident control and Crisis management (EMRIC)

EMRIC ia a unique collaboration of public services, that are responsible for public safety, including fire services, technical assistance and emergency medical care in their respective territories.

In a region that is so rich of borders, like the Euregion Meuse-Rhine, emergency services from abroad can often be at the scene of the incident faster than own services. When every second counts, fast assistance is vital.

The collaborating servcies are the fire services of Aachen, the Ordnungsamt from Kreis Heinsberg and the Ordnungsamt from the Städteregion Aachen in Germany, de Province of Limburg and Liège in Belgium and the Veiligheidsregio and GGD Zuid-Limburg in the Netherlands. These are the organisations that fund the collaboration and the so-called EMRIC office. In addition to these seven partners, over 30 services and governments are involved in the EMRIC collaboration.

EMRIC ensures that cross-border collaboration is possible, however, self-evident it is in the least.

Within these three countries, operational and legal systems differ to such extent, that a lot needs to be arranged, before ambulance or fire trucks are allowed to cross the border. In a region that is so rich of borders, like the Euregion Meuse-Rhine, working, recreating and studying across the border has become self-evident, however, this was not the case for assisting each other in case of emergencies.

More Info:

GROS

(Transnational civil protection collaboration)

Involved parties are the Dutch Safety Regions Drenthe, Twente and IJsselland, the Technisches Hillswerk and Landesverband Bremen / Niedersachsen.

Purpose: Provide cross-border incident response and create cooperation agreements focused on information sharing and international assistance.

In the international initiative GROS (agreement for cross-border cooperation)

subjects such as international exercises, response planning, knowledge sharing and international assistance are discussed. Together with the Safety Regions Twente and Drethe, IJsselland cooperates with Germany with regards to the nuclear plant in Lingen. A shared incident response plan exists, the Katastrophenschutz-Sonderplan KKE Kreis Emsland. In the cross-border assistance agreement of the Technisches Hillswerk and Landesverband Bremen / Niedersachsen the daily deployment of Dutch emergency services in Germany and vice versa is arranged.

In addition, several networks have been created to different civil protection topics, for example in the context of the FIRE-IN project or the DRIVER+ project. The FIRE-IN project developed several fire-related working groups, e.g. on structure fires, wildfires or CBRN aspects. The DRIVER+ Crisis Management Innovation Network Europe (CMINE) encompasses thematic groups among others on wildfires and volunteer management.

Particularly in the CBRN domain, a range of activities have been implemented over the past years to facilitate multi-national collaboration:

- The “End-user driven DEmo for cbrNE” (EDEN) project has addressed several CBRNE related aspects. Among others, it analysed the legal and policy framework for CBRNE response (D82-1) and developed a CBRNE related communication kit.

- The European CBRNE Innovation for the Market Cluster (ENCIRCLE) project developed a web catalogue of CBRNE related solutions and specified the related network of suppliers, users, Research and Technology Organisations (RTOs) and training centres.

- European Reference Network for Critical Infrastructure Protection (ERNCIP), coordinated by the JRC:

The European Reference Network for Critical Infrastructure Protection (ERNCIP) aims at providing a framework within which experimental facilities and laboratories will share knowledge and expertise in order to harmonise test protocols throughout Europe, leading to better protection of critical infrastructures against all types of threats and hazards and to the creation of a single market for security solutions.

The Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear Risk Mitigation Centres of Excellence (CBRN CoE) is an EU initiative. It is led, financed and implemented by the European Commission, in close coordination with the European External Action Service (EEAS) and with the support of the UN (UNICRI) and other International Organisations and local experts. The funding for CoE projects comes from the EU Instrument Contributing to Security and Peace (IcSP).

The CoE is centred around a worldwide network of local experts and collaborating partners. In avoiding a traditional top-down approach, we work in partnership with countries to encourage local ownership of CBRN action plans, policies and project proposals. Based on the EU CBRN CoE prescribed methodology, CBRN CoE NFPs and their CBRN National Teams are responsible for assessing their respective national needs. Following the assessment, National Teams develop their own National Action Plans with the ultimate goal of developing an integrated and effective CBRN policy that is in line with internationally agreed standards. Where gaps are identified the CoE aims to work with the countries to address any possible shortcomings by means of tailored regional projects.

Technology

Information Sharing Examples – National Level

Netherlands:

Dutch Nation Wide Crisis Management System (LCMS)

LCMS is a nation-wide crisis management system used in The Netherlands to maintain and share a common operational picture supporting large-scale crisis management collaboration.

LCMS is used by all 25 safety regions, the majority of the waterboards, Rijkswaterstaat, Learn More

an increasing number of emergency health care organisations, the Royal Military Police organisation and some drinking water providers. LCMS supports netcentric collaboration, which is a way of working in which clear agreements are made about sharing information so that decision-making under (crisis) circumstances is always based on an up-to-date, consistent and common operational picture. LCMS is a web based collaboration environment with a very high level of availability. The environment can be used to share information within an organisation as well as between organisations. It supports maintaining and sharing geographical as well as textual pictures.

More Info:

UK:

JESIP

Joint Doctrine developed in the UK encompasses – among others – a section on communication.

It builds on the following principles: Learn More

The following supports successful communication between responders and responder agencies:

– Exchanging reliable and accurate information, such as critical information about hazards, risks and threats

– Ensuring the information shared is free from acronyms and other potential sources of confusion

– Understanding the responsibilities and capabilities of each of the responder agencies involved

-Clarifying that information shared, including terminology and symbols, is understood and agreed by all involved in the response

Joint symbols as well as joint terminology is used:

emergency-responder-interoperability-lexicon

Civil_Protection_Common_Map_Symbology_V1-0_March_2012.pdf

Furthermore, all organisations follows the METHAN/principle:

M/ETHANE is now the recognised common model for passing incident information between services and their control rooms.

All services have used similar models for passing information in the past but JESIP has instigated the use of a common model which will mean information can be shared in a consistent way, quickly and easily, whoever the information is passing between.

More Info:

Portugal:

Integrated System for Relief and Protection Operations (SIOPS)

SIOPS is a set of rules and procedures, which guarantee that civil protection agents act, at the operational level, in a coordinated way and under a unique command.

SIOPS is facilitated by inter-organisational command centres: Learn More

the National Coordination Centre (CCON) district coordination centres using a joint software for situation assessment.

US & CANADA

Incident Command System (ICS)

Incidents Command Systems play an important role in managing (multi-organisational) incidents efficiently.

One of the most prominent examples is the ICS applied for example in the U.S. and Canada.

The Incident Command System (ICS) is a standardized on-site management system designed to enable effective, Learn More

efficient incident management by integrating a combination of facilities, equipment, personnel, procedures, and communications operating within a common organizational structure.

The ICS is used to manage an incident or a non-emergency event, and can be used equally well for both small and large situations.

ICS Canadana for example is a Pan Canadian command and control structure used to help manage emergency incidents and planned events. It provides the framework for standard incident management response and improves interoperability between all response organizations as well as with international cooperators.

More Info:

Information Sharing Examples – Multi-National Level

Host Nation Support (HNS) Guidelines

Standards for requesting and receiving international assistance.

Host Nation Support “implies all actions undertaken in the preparedness phase and the disaster response management by a Participating State, Learn More

receiving or sending assistance, or the Commission, in order to remove as much as possible any foreseeable obstacle to international assistance so as to ensure that disaster response operations proceed smoothly” (European Commission 2012, p. 3).

Derived both from experience and lessons learnt from emergencies, exercises, and trainings, the EU has developed Host Nation Support Guidelines (HNSG) that intend to assist affected UCPM member states in the organization of the assistance that they receive. Aiming to provide support and guidance, EU HNSG are complementary to existing international documents in the context of disaster management and relief operations, and are of a non-binding nature. They can be applied both in the context of UCPM operations within the EU, as well as in the context of bilateral assistance from an European state to a non-European state. The EC also advocates regard for the HNSG by non-European states requesting and receiving international assistance through the UCPM. [p.3]

The Guidelines lay out advice regarding HNS on the four areas of emergency planning, emergency management and co-ordination on site, logistics/transport, and legal and financial issues. [p.4ff]. The EU HNSG recommend the use of checklists and templates for the Host Nation Support process, as well as coherent use of terminology. To this end, the HNS Guidelines include templates (such as for the request for international assistance, and the offer of international assistance), a HNS checklist, and a glossary of terms in the Annexes. [p.9ff]

More Info:

UN-OCHA – UNDAC:

United Nations Disaster Assessment and Coordination Field Handbook

The UNDAC system was originally established in 1993 by United Nations (UN) and the International Search and Rescue Advisory Group (INSARAG) to help the United Nations and governments of disaster-affected countries during the first phase of a sudden-onset emergency. UNDAC teams can deploy at short notice (12-48 hours) anywhere in the world and serve as a first point of contact for incoming international relief onsite or at national level.

UNDAC thus supports effective coordination between national disaster management agencies and incoming search and rescue teams (see team classification in INSARAG Guidelines). Learn More

Specifically in response to earthquakes, UNDAC teams set up and manage the On-Site Operations Coordination Centre (OSOCC) to help coordinate international Urban Search and Rescue (USAR) teams. Among the technical services that UNDAC provides, the principal ones are on-site coordination and information dissemination services, under the leadership of the affected country.

The Field Handbook is intended as an easily accessible reference guide for members of an UNDAC team before and during a mission to a disaster or emergency, covering the following topics:

A. The international emergency environment; B. The UNDAC Concept; C. Pre-mission; D. On-mission; E. Mission end; F. Team management; G. Safety and security; H. Information management planning; I. Assessment and analysis (A&A); J. Reporting and analytical outputs; K. Media; L. Coordination; M. OSOCC concept; N. Coordination cells; O. Regional approaches; P. Disaster logistics; Q. ICT and technical equipment; R. Facilities; S. Personal health.

More Info:

Information Sharing – General ethical, privacy, and data protection considerations

- When sharing data, encourage working groups that consider data sharing priorities, responsibilities, and how information will be shared and used.

- Assess what data can and should be shared across boundaries. Consider carefully what to do with data that is gathered but cannot be processed or exchanged due to security or privacy rights (Kenk, Križaj, Štruc, & Dobrišek 2013).

- Assess how any information gathered supports responders’ duty of care responsibilities. It is important to make sure that the duty to provide care is not obscured by the focused attention on what data collaborators have and what is involved in sharing it.

- Training and planning for the recovery phase could be neglected if the shareable data categories overemphasize crisis response.

- Information technology, their categories and ontologies, should be designed in ways that don’t privilege cultural norms (e.g. one country’s way of defining demographics), at the exclusion of less privileged groups (e.g. missing a race or ethnicity category; defining tactics using the Italian system but not the Dutch system) (Veale et al 2018).

- Information systems are always just approximations of the world; they encourage users to pay attention in specific ways, grounded in specific value systems and implicit biases (GFDRR, 2018; Bowker et al., 2010).

- Commonalities can sometimes come at the expense of important differences. Unintentional biases can emerge from lack of societal diversity considerations to accommodate EU inclusivity, particularly when managing classification schemes and ontologies from across different cultural and organisational borders to find consensus.

- If cities, regions, or nations are not prepared with the appropriate data for the tools they are using to collaborate with, then vulnerable people could be either deprioritised using data from a different location where they are not well represented or situation or could be falsely prioritised based on incomplete data. Without detailed consideration, this also shifts energy from resources and boots-on-the-ground to work with data.

- If using tools, establish mandatory third-party validation of data analytic systems to periodically check their effectiveness, mitigated biases, continually improve the system’s ability to support collaboration, and help the system learn to look forwards to future, unknown, events with unfamiliar actors.

- Organisations and responders should establish questions to ask of the data in transboundary crisis activities and how to ensure transparency between partners when different classification schema might affect information sharing or the generalizability of model and algorithmic results (GFDRR, 2018).

Standard Operating Procedures

Standard Operating Procedures Examples – National Level

Ireland:

M.E.M. Framework, Dedicated Guidance Documents

Guidance Document 10 – A Guide for PRA Local Competent Authorities under S.I No.209 of 2015 European Communities (Control of Major Accident Hazards Involving Dangerous Substances) Regulations 2015

More documents e.g. on Flood Emergencies, Motorway and Dual Carriage Emergencies, etc. can be found here: LINK

Guidance Document 10 is primarily concerned with the obligations and responsibilities of the relevant Principal Response Agencies with regard to External Emergency Planning for ‘Seveso’ Upper Tier Establishments.

It is requested that comments and observations that arise during exercises or real incidents are fed back to the national level.

More Info:

UK:

JESIP Joint Working (Joint Decision Making)

Decision making in incident management follows a general pattern of:

Working out what’s going on (situation),

Establishing what you need to achieve (direction)

Deciding what to do about it (action), all informed by a statement and understanding of overarching values and purpose.

One of the difficulties facing commanders from different responder agencies is how to bring together the available information, reconcile potentially differing priorities and then make effective decisions together.

The Joint Decision Model (JDM), shown below, was developed to resolve this issue.

Responder agencies may use various supporting processes and sources to provide commanders with information, including information on any planned intentions, to commanders. This supports joint decision making.

All joint decisions, and the rationale behind them, should be recorded in a ‘joint decision log’.

When using the joint decision model, the first priority is to gather and assess information and intelligence.

Responders should work together to build shared situational awareness, recognising that this requires continuous effort as the situation, and responders’ understanding, will change over time.

Understanding the risks is vital in establishing shared situational awareness, as it enables responders to answer the three fundamental questions of ‘what, so what and what might?’

Once shared situation awareness is established, the preferred ‘end state’ should be agreed as the central part of a joint working strategy. A working strategy should set out what a team is trying to achieve, and how they are going to achieve it.

More Info:

Standard Operating Procedures Examples – Multi-National Level

Maritime Incident Response Groups (MIRG)

Initiative by the International Maritime Rescue Federation (IMRF) to help with the sharing of knowledge information, initiatives and contacts on this particular topic.

There are two main working groups under this umbrealla: the Baltic and the Adriatic MIRG.

The Baltic Sea MIRG was created as a project by the Finnish Border Guard as the responsible maritime search and rescue authority in cooperation with Finland’s Emergency Rescue Services. The project has sought to create joint MIRG coordination models and operational guidelines for the Baltic Sea region and support the harmonisation of MIRG services in Europe. It developed material on MIRG Services and Training in Europe, European Maritime Traffic Risk Assessment on Ship Fires, Ship Fire Incident Analysis, Operational Guidelines for International MIRG Operations which can be found here: https://www.raja.fi/projects/past/mirg

The North Adriatic Maritime Response Group (NAMIRG) aims at establishing a North Adriatic efficient system of emergency response by the intervention of a trained and specially equipped squad of fire fighters, who can be transported on board of a helicopter to ships on fire at sea: https://www.namirg.eu/

At the European level the MIRGS are bridged by an umbrella which brings together four Maritime Incident Response Groups: http://www.mirg.eu/

More Info:

UN-INSARAG

(International Search and Rescue Advisory Group)

Historically following the earthquakes in Armenia in 1988 and Mexico 1985, specialised international Urban Search and Rescue (USAR) teams who worked together in the disaster relief operations initiated the International Search and Rescue Advisory Group (INSARAG).

INSARAG is an inter-governmental humanitarian network of disaster managers, government officials, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and practitioners in the field of Urban Search and Rescue operating under the umbrella of the UN. Within the realm of the UN’s mandate, INSARAG contributes to the implementation of the International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (ISDR).

USAR assistance is designed to especially respond to emergencies characterised by collapsed structures in urban environments.

USAR teams are equipped to provide emergency medical care to survivors trapped in collapsed structures, and assist in victim search, debris removal, detection of hazardous materials, and stabilization of damaged structures in the context of their search and rescue operations (UNOCHA 2015, p. 17). The INSARAG Guidelines are based on INSARAG members’ best practices and lessons learnt, and aim to ensure “high quality support in the critical life-saving activity of search and rescue in the immediate aftermath of a disaster“ (p.4).

More Info:

ChemSAR:

Operational Plans and Procedures for Maritime Search and Rescue in HNS Incidents

Currently there is a lack of operational plans and standard operational procedures (SOP) for search and rescue (SAR) operations applicable to cases of hazardous and noxious substances (HNS) incidents in Baltic Sea Region (BSR) according to rescue authorities and study reports.

The project created operational plans and standard operational procedures (SOP) needed in SAR operations of HNS incidents.

By creating plans and SOPs for the rescue operations related to maritime HNS incidents the project will tackle the above mentioned lack of operational procedures.

By developing the e-learning material for the different international actors in the rescue operations the project will enhance and harmonize the level of know-how to ensure safe rescue operations. The chemical data bank will act as the basis for information seeking in rescue operations and e-learning.

More Info:

In addition, several networks have been created to different civil protection topics, for example in the context of the FIRE-IN project or the DRIVER+ project. The FIRE-IN project developed several fire-related working groups, e.g. on structure fires, wildfires or CBRN aspects. The DRIVER+ Crisis Management Innovation Network Europe (CMINE) encompasses thematic groups among others on wildfires and volunteer management: LINK

Particularly in the CBRN domain, a range of activities have been implemented over the past years to facilitate multi-national collaboration:

- The “End-user driven DEmo for cbrNE” (EDEN) project has addressed several CBRNE related aspects. Among others, it analysed the legal and policy framework for CBRNE response (D82-1) and developed a CBRNE related communication kit: LINK

- The European CBRNE Innovation for the Market Cluster (ENCIRCLE) project developed a web-catalogue of CBRNE related solutions and specified the related network of suppliers, users, Research and Technology Organisations (RTOs) and training centres.

- European Reference Network for Critical Infrastructure Protection (ERNCIP), coordinated by the JRC:

The European Reference Network for Critical Infrastructure Protection (ERNCIP) aims at providing a framework within which experimental facilities and laboratories will share knowledge and expertise in order to harmonise test protocols throughout Europe, leading to better protection of critical infrastructures against all types of threats and hazards and to the creation of a single market for security solutions: LINK

The Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear Risk Mitigation Centres of Excellence (CBRN CoE) is an EU initiative. It is led, financed and implemented by the European Commission, in close coordination with the European External Action Service (EEAS) and with the support of the UN (UNICRI) and other International Organisations and local experts. The funding for CoE projects comes from the EU Instrument Contributing to Security and Peace (IcSP).

The CoE is centred around a worldwide network of local experts and collaborating partners. In avoiding a traditional top-down approach, we work in partnership with countries to encourage local ownership of CBRN action plans, policies and project proposals. Based on the EU CBRN CoE prescribed methodology, CBRN CoE NFPs and their CBRN National Teams are responsible for assessing their respective national needs. Following the assessment, National Teams develop their own National Action Plans with the ultimate goal of developing an integrated and effective CBRN policy that is in line with internationally agreed standards. Where gaps are identified the CoE aims to work with the countries to address any possible shortcomings by means of tailored regional projects.

Standard Operating Procedures Examples – Ethical considerations

Intercultural ethical issues or local values cannot be readily addressed or wiped away by standards. It is important to establish joint protocols for all activities to ensure successful collaboration and management of ethical and privacy issues which may arise. With these:

- Provide (customisable) glossaries/keys for icons and data categories used.

- Provide clear explanations of what each data category means.

- Provide sources for where categories, icons, and standards came from and document why these were chosen and considered representative for multi-hazard situations across Europe.

- Provide guidance and best practices to support users in seeing necessary differences.

- Include regular practices for configuring awareness (http://www.isitethical.eu/portfolio-item/configuring-awareness/).

Training and Exercises

Training and Exercises Examples – National Level

IRELAND – M.E.M.

Framework for Major Emergency Management

A Guide to Planning and Staging Exercises

The Framework for Major Emergency Management was developed in 2005 and was adopted by Government decision in 2006. Its purpose is to set out common arrangements and structures for front line public sector emergency management in Ireland.

The document provides guidance in planning and implementing multi-agency exercises

More Info:

UK – JESIP Framework

Testing and Exercising Assurance Framework

The findings from a number of reviews of major national emergencies and disasters made clear that the emergency services carry out their individual roles efficiently and professionally.

However, there were some common themes relating to joint working where improvement was needed – JESIP was established to address these issues:Learn More

- Challenges with initial command, control and coordination activities on arrival at scene

- A requirement for common joint operational and command procedures

- Role of others, especially specialist resources and the reasons for their deployment, not well understood between services

- Challenges in the identification of those in charge at the scene leading to delays in planning response activity

- Misunderstandings when sharing incident information and differing risk thresholds not understood

This framework is based on the model used by JESIP for the validation exercises run as part of the initial programme. This template should help exercise planners achieve cost-effective exercising of multiple groups of commanders in a live-play environment in a single day.

More Info:

Training and Exercises Examples – Multi-National Level

EU Civil Protection Mechanism Training Programme

The EU Civil Protection Mechanism runs an active and comprehensive training programme,Learn More

offering experts from all over Europe a deeper knowledge of the requirements of European civil protection missions. The training helps experts improve their coordination and assessment skills in disaster response.

A training programme has been set up for civil protection and emergency management personnel to enhance prevention,

preparedness and disaster response by ensuring compatibility and complementarity between the intervention teams and other intervention support as well as by improving the competence of the experts involved. Since 2004 over 8 000 training course places have been offered to Participating States, EU staff, partner organisations and third countries.

The basis of all training courses is a comprehensive online learning package that gives experts the opportunity to prepare prior to course participation and to refresh their knowledge.

The training courses under the Union Civil Protection Mechanism are meant as a supplement to the national training (expert training and the needed basic training for international deployments) provided to the experts by their home country or organisation. The different courses are described in the brochure available via the indicated link.

More Info:

eNOTICE

The scope of the H2020 SEC-21–GM-2016-2017 eNOTICE project – European Network of CBRN Training Centers – is to build a dynamic,Learn More

functional and sustainable pan European network of CBRN Training Centres, testing and demonstration sites (CBRN TC), aiming at enhanced capacity building in training and users-driven innovation and research, based on well-identified needs.

eNOTICE offers to map and label EU CBRN Training Centers, based on their capabilities and specificities; Learn More

to use a dedicated web based information and communication platform for exchange of effective practices, lessons learned and dissemination; to pool and share resources. invite current R&D projects to tests and demos at eNOTICE training centres at our Joint Activities. 09/2017- 08/2022

More Info:

Usage

Collaboration in Daily Business Examples – National Level

UK:

JESIP

In the UK, jont doctrine (JESIP) was developed following the Civil Contingencies Act and the Pollock Report

The Civil Contingencies Act 2004 provides a single framework for civil protection and seeks to reinforce partnership working at all levels. It recognises that interrelated systems provide essential services in the UK and as networks have become more complex the range of challenges in maintaining resilience has broadened. Such complexity requires collaborative partnerships working towards common outcomes. Thus the expectation of the Act is that local authorities, the emergency services and the health sector, along with other key service providers, will collaborate and be able to provide normal services in crises, so far as is reasonably practicable.

The key components of the Joint Doctrine are:

Principles for Joint Working – the principles we expect commanders to follow when planning a joint incident response

M/ETHANE – a common method for passing incident information between services and their control rooms

Joint Decision Model (JDM) – A common model used nationally to enable commanders to make effective decisions together

More Info:

UK:

Local resilience forums were developed

There is more information for local resilience forums, including on self-assessment, peer review and improvement, in The role of Local Resilience Forums: a reference document.

Local resilience forums (LRFs) are multi-agency partnerships made up of

representatives from local public services, including the emergency services, local authorities, the NHS, the Environment Agency and others. These agencies are known as Category 1 Responders, as defined by the Civil Contingencies Act.

More Info:

Resilience Direct Online Network

The Civil Contingencies Act 2004 requires that emergency responders co-operate and share information

in order to efficiently and effectively prepare for, and respond to, emergencies and ensure that action is coordinated. ResilienceDirect helps organisations to fulfil these duties by supporting the adoption of common working practices, and ensuring that key information is readily and consistently available to users.

ResilienceDirect is an online private ‘network’ which enables civil protection practitioners to work together – across geographical and organisational boundaries – during the preparation, response and recovery phases of an event or emergency.

More Info:

Netherlands:

Dutch Nation Wide Crisis Management System (LCMS)

LCMS is a nation-wide crisis management system used in The Netherlands to maintain and share a common operational picture supporting large-scale crisis management collaboration.

LCMS is used by all 25 safety regions, the majority of the waterboards, Rijkswaterstaat, an increasing number of emergency health care organisations, the Royal Military Police organisation and some drinking water providers.

LCMS supports netcentric collaboration, which is a way of working in which clear agreements are made about sharing information so that decision-making under (crisis) circumstances is always based on an up-to-date, consistent and common operational picture. LCMS is a web-based collaboration environment with a very high level of availability. The environment can be used to share information within an organisation as well as between organisations. It supports maintaining and sharing geographical as well as textual pictures.

More Info:

SAMIJ:

Samenwerkingsregeling Incidentbestrijding IJsselmeergebied

The SAMIJ agreement was signed in 2010 by all involved parties. The platform created a shared incident response plan for the Lake IJssel in 2011.

The network is formally led by a governmental board, and managed by an operational working group. The working group organizes yearly multidisciplinary exercises, updates the incident response plan and corresponding scenarios. They also organize thematic meetings and are responsible for creating a long-term vision for future developments. All partners contribute financially to the network.

Samenwerkingsregeling Incidentbestrijding IJsselmeergebied (SAMIJ) is a network organisation,

involved parties are 9 Safety Regions, 6 Regional Water Boards, the Coast Guard, National Police, the Rescue Guard and The Directorate-General for Public Works and Water Management. All parties have an individual responsibility within incident response on the Lake IJssel. The goal is to form cooperation agreements between these parties in order to improve incident response on the Lake IJssel.

More Info:

Collaboration in Daily Business Examples – Multi-National Level

Euregion Meuse-Rhine Incident control and Crisis management (EMRIC)

EMRIC ia a unique collaboration of public services, that are responsible for public safety, including fire services, technical assistance and emergency medical care in their respective territories.

In a region that is so rich of borders, like the Euregion Meuse-Rhine, emergency services from abroad can often be at the scene of the incident faster than own services. When every second counts, fast assistance is vital.

The collaborating servcies are the fire services of Aachen, the Ordnungsamt from Kreis Heinsberg and the Ordnungsamt from the Städteregion Aachen in Germany, de Province of Limburg and Liège in Belgium and the Veiligheidsregio and GGD Zuid-Limburg in the Netherlands. These are the organisations that fund the collaboration and the so-called EMRIC office. In addition to these seven partners, over 30 services and governments are involved in the EMRIC collaboration.

EMRIC ensures that cross-border collaboration is possible, however, self-evident it is in the least.

Within these three countries, operational and legal systems differ to such extent, that a lot needs to be arranged, before ambulance or fire trucks are allowed to cross the border. In a region that is so rich of borders, like the Euregion Meuse-Rhine, working, recreating and studying across the border has become self-evident, however, this was not the case for assisting each other in case of emergencies.

More Info:

ChemSAR:

Operational Plans and Procedures for Maritime Search and Rescue in HNS Incidents

Currently there is a lack of operational plans and standard operational procedures (SOP) for search and rescue (SAR) operations applicable to cases of hazardous and noxious substances (HNS) incidents in Baltic Sea Region (BSR) according to rescue authorities and study reports.

The project created operational plans and standard operational procedures (SOP) needed in SAR operations of HNS incidents.

By creating plans and SOPs for the rescue operations related to maritime HNS incidents the project will tackle the above mentioned lack of operational procedures.

By developing the e-learning material for the different international actors in the rescue operations the project will enhance and harmonize the level of know-how to ensure safe rescue operations. The chemical data bank will act as the basis for information seeking in rescue operations and e-learning.

More Info: